In the year 2016, one might assume that education for those who are d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing has advanced to the point where deaf young people in America are receiving the same level of education as their hearing peers. One might assume that federal legislation such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) does enough to protect deaf/HoH children’s right to expand their minds while developing valuable cultural and practical skills in a safe, productive environment. One might have faith that the education system of our modern society has evolved to accommodate the diverse needs of an increasingly diverse population.

In the year 2016, one might assume that education for those who are d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing has advanced to the point where deaf young people in America are receiving the same level of education as their hearing peers. One might assume that federal legislation such as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) does enough to protect deaf/HoH children’s right to expand their minds while developing valuable cultural and practical skills in a safe, productive environment. One might have faith that the education system of our modern society has evolved to accommodate the diverse needs of an increasingly diverse population.

Upon closer observation, however, we see that education programs for deaf and otherwise disabled individuals in this country are in an unfortunate state, and in even further jeopardy as more children are enrolled in mainstream schools that are underfunded, lacking in support, and simply not equipped for people with specialized educational requirements. To aid in the progress of our multicultural society, we all must become aware of the institutionalized injustices that perpetuate oppression, and then we must work together to change these structures— from both the top down, and from the bottom up. Before people begin working toward a solution, it is crucial to first identify the root of the problem.

Building a Solid Foundation

Access to education is an issue that most people who are deaf/ HoH begin to face long before they set foot in a school. Since 9 out of 10 deaf children are born to hearing families, these kids often begin their journey without acquiring basic communication skills, as their families don’t use sign language. Deaf babies who do not have access to a signed language cannot easily articulate their wants and needs with caregivers, and therefore they can become quickly frustrated. Falling behind their hearing peers in early linguistic comprehension causes many deaf youths to face a disadvantage right from the start. This is where schools for the Deaf can make all the difference by offering young deaf children the support they need to develop their language and literacy skills in a specifically structured setting.

Access to education is an issue that most people who are deaf/ HoH begin to face long before they set foot in a school. Since 9 out of 10 deaf children are born to hearing families, these kids often begin their journey without acquiring basic communication skills, as their families don’t use sign language. Deaf babies who do not have access to a signed language cannot easily articulate their wants and needs with caregivers, and therefore they can become quickly frustrated. Falling behind their hearing peers in early linguistic comprehension causes many deaf youths to face a disadvantage right from the start. This is where schools for the Deaf can make all the difference by offering young deaf children the support they need to develop their language and literacy skills in a specifically structured setting.

“For over 130 years, the Deaf community have been fighting for Deaf Education to be optimized for each Deaf child, but the medical and educational system have consistently failed the Deaf children because of lack of full access to language acquisition,” explains Julie Rems-Smario, Founding Executive Director of DeafHope, President of California Association of the Deaf, and co-founder of the grassroots organization Language Equality and Acquisition for Deaf Kids (LEAD-K). “It is not the ‘deafness’ that causes the child to be language deprived. It is the lack of full access to language acquisition, especially during first two years, that causes the Deaf child to be language-deprived.”

Both scientific research and personal anecdotes have shown the positive impact of Deaf schools. In this environment, whether it is a day school or a residential school, children who are deaf are more likely to have their emotional, social, and educational needs met by a qualified staff. In Deaf schools, children who are deaf are able to connect with others who share the experience of deafness. They will be exposed to more deaf role models and/or potential mentors, and may themselves become a mentor for another deaf young person. Immersed in a Deaf cultural institution, children can develop a strong self-identity and sense of pride in something they may have once felt ashamed of.

Both scientific research and personal anecdotes have shown the positive impact of Deaf schools. In this environment, whether it is a day school or a residential school, children who are deaf are more likely to have their emotional, social, and educational needs met by a qualified staff. In Deaf schools, children who are deaf are able to connect with others who share the experience of deafness. They will be exposed to more deaf role models and/or potential mentors, and may themselves become a mentor for another deaf young person. Immersed in a Deaf cultural institution, children can develop a strong self-identity and sense of pride in something they may have once felt ashamed of.

“Deaf schools are not just an educational option, but are the only beneficial placement for many deaf children,” states the National Association for the Deaf (NAD) position statement on Schools for the Deaf. “Deaf schools, an integral part of American history, have not only received quality education but also benefited from the fostering of its culture, heritage, and language through such essential institutions. Schools for the deaf, including charter schools founded to serve deaf children, are uniquely capable of providing the necessary visual learning environment and the ideal conditions for language development for deaf children.”

There is ample evidence to support American Sign Language (ASL)/ English bilingualism as an optimal solution for deaf children, especially those in hearing families. Research shows higher educational outcomes for deaf children who have access to visual language, even those who are being raised to vocalize or who have a Cochlear Implant. The benefits of Deaf schools are undeniable, yet these programs are seeing budget cuts and lowered enrollment numbers all across the country as parents are steered toward mainstreamed education options. There are currently around 100 schools for the deaf in the United States. Since the year 2000, seven state schools for the deaf have closed down— most of these either pre-K-12 or K-12 programs.

Why Deaf Schools?

“Placing every deaf child in their respective neighborhood school is not practical, economical, or educationally beneficial,” asserts the NAD position statement. It continues to explain that mainstream schools with few deaf students tend to lack the appropriate resources. “In many states, there are large geographical areas with a small deaf student population, making schools for the deaf a cost-effective means to optimal educational services.”

“Placing every deaf child in their respective neighborhood school is not practical, economical, or educationally beneficial,” asserts the NAD position statement. It continues to explain that mainstream schools with few deaf students tend to lack the appropriate resources. “In many states, there are large geographical areas with a small deaf student population, making schools for the deaf a cost-effective means to optimal educational services.”

When students are enrolled in a mainstream school, they are entitled to create an Individualized Education Program (IEP) with teachers and administrators that is designed to meet their needs; this may include interpreters and note-takers in the classroom. While IEPs are great in theory, in practice they tend to lack resources and long term support, failing to offer deaf/HoH kids an equal opportunity to receive an education. According to Tawny Holmes, Education Policy Counsel at the NAD, recent years have seen downsizing in education programs for deaf children across the board, further isolating already isolated youths in the mainstream system.

“[There has been] a huge shift to ‘solitaire’ education,” Holmes explains. “By that I mean, not only do schools for the deaf have declining numbers, but many large mainstream programs are closing. So that means an increased number of deaf/hard of hearing students are isolated in their public school- ‘the only deaf student in the school.’ This is confirmed by the Gallaudet Research Institute [survey] results.”

Students Bear The Consequences

Research suggests that isolation and a lack of educational support results in overall lower test scores and reading levels for deaf young people. For more than half a century, the average reading level among deaf adults has hovered around the 3rd or 4th grade level, compared to 7th or 8th grade for the general population of adult Americans. According to Sheri A. Farinha, CEO of NorCal Services for Deaf & Hard of Hearing, and co-founder of LEAD-K: the 2008 California English Language Arts K-12 statistics showed that less than 15% hard of hearing students, and less than 6% deaf students, are able to read and write proficiently.

Research suggests that isolation and a lack of educational support results in overall lower test scores and reading levels for deaf young people. For more than half a century, the average reading level among deaf adults has hovered around the 3rd or 4th grade level, compared to 7th or 8th grade for the general population of adult Americans. According to Sheri A. Farinha, CEO of NorCal Services for Deaf & Hard of Hearing, and co-founder of LEAD-K: the 2008 California English Language Arts K-12 statistics showed that less than 15% hard of hearing students, and less than 6% deaf students, are able to read and write proficiently.

In mainstream settings, where classrooms may be brimming with different students who have all different abilities and teachers are often under pressure to get students prepared for state exams, the unique needs of deaf students can get overlooked despite educator’s best intentions. These children quietly fall behind without easy access to remedial tools, such as tutoring or mentorship. They frequently struggle with feeling intellectually inferior, when they are actually just experiencing communication barriers. In schools, the interpreter may become their only ally and resource— viewed by the young person as a teacher, language model, advocate, and conduit between the student and the rest of the classroom. Unless teachers are provided thorough cultural competency training and are offered ongoing professional development opportunities that focus on academic inclusion, it’s unlikely that they will be prepared to accommodate the educational and social needs of children who are deaf. This disconnect can keep deaf students in mainstream schools from ever forming a real relationship with their teachers, peers, or the educational experience.

The effects of poor education, of course, ripple out into the community at large. Kids who feel ostracized by the system tend to work outside of it, instead. Around 60% of juvenile delinquents in California have disabilities. According the the US Department of Justice, nationwide, “an estimated 32% of prisoners and 40% of jail inmates reported having at least one disability,” with about 7% of all those surveyed self-reporting a hearing deficit. Helping Educate to Advance the Rights of the Deaf (HEARD) has found that there are no official statistics regarding the number of deaf individuals in prison, but their organization has located more than 500 deaf prisoners who have gotten caught up in a legal system that offers them little justice.

Deaf individuals continue to face exponentially higher unemployment rates and many reluctantly rely on social services for basic survival while seeking sustainable employment opportunities. Instead of investing in deaf education and cultural competency training programs, thus changing the potential outcome for generations to come, the system effectively perpetuates a cycle of dependence. Grassroots and community-led organizations have been gaining momentum over the past few years as citizens attempt to pick up the pieces where the existing infrastructure has failed.

Deaf individuals continue to face exponentially higher unemployment rates and many reluctantly rely on social services for basic survival while seeking sustainable employment opportunities. Instead of investing in deaf education and cultural competency training programs, thus changing the potential outcome for generations to come, the system effectively perpetuates a cycle of dependence. Grassroots and community-led organizations have been gaining momentum over the past few years as citizens attempt to pick up the pieces where the existing infrastructure has failed.

“An increased number of D/HoH students do not have access to qualified interpreters, teachers of the deaf, nor peers/role models. Nor do they receive information or knowledge on self-advocacy, community support and resources,” Holmes says. “We [at NAD] have been receiving increased distress by parents, teachers, and community members on not being able to secure services for the deaf/ HoH children they have or see. Our intake requests in this area has increased by 500% in the past three years.”

Deaf Education Needs More Deaf Leadership

Mainstream education programs are severely lacking in a deaf perspective, and this has been a major source of oppression since the Milan Conference in 1880, when a group of  hearing individuals decided the unfortunate course of deaf education for the next 100+ years. In this modern era, however, deaf people have the technology to connect and organize like never before. We are currently witnessing a major push-back against hearing parties making decisions for the deaf community, with assertive advocates utilizing new communication tools to rally support for proactive deaf-led reform. They are sharing their own experiences with the families of deaf children, alongside supporting research, to help secure better opportunities for generations to come.

hearing individuals decided the unfortunate course of deaf education for the next 100+ years. In this modern era, however, deaf people have the technology to connect and organize like never before. We are currently witnessing a major push-back against hearing parties making decisions for the deaf community, with assertive advocates utilizing new communication tools to rally support for proactive deaf-led reform. They are sharing their own experiences with the families of deaf children, alongside supporting research, to help secure better opportunities for generations to come.

Community organizations are emerging as important resources and beacons of hope for the families of children who are deaf. By providing easily accessible information from a deaf perspective, these organizations hope to demystify deafness and raise awareness about issues that impact the community. One of the most important issues being a child’s human right to a language they can use. Without access to language, a child’s learning will inevitably be delayed. Deciding it was time for a new course of action, in 2011 Rems Smario and Farina envisioned a legislative plan for addressing language deprivation. They invited a group of a group of stakeholders in California including parents, educators, and community members to cultivate the LEAD-K movement.

“The goal of the LEAD-K movement is to create generations of Kindergarten-ready Deaf children,” Rems-Smario explains. “To make this a reality the LEAD-K stakeholders strategized to pass a state law to enforce language acquisition milestones and accountability for all Deaf babies during the first five years of their lives so they are ready for literacy, reading and writing, when they enroll in their Kindergarten class.”

According to their website, LEAD-K’s strategies are twofold:

1) Raise the awareness and understanding of the general public, parents, and the education system of the Deaf child’s experience in language learning, the role of visual learning for a Deaf child and how that impacts their educational success; and

2) To work with other partners to change public policy related to the education of Deaf children who use ASL and English, both or one of the languages toward Kindergarten-readiness.

Within just nine months, LEAD-K made a strong legislative impact by passing laws in three states. California became the first state to pass the language acquisition accountability law, SB 210, which was authored by Senator Galgiani and signed into law by Governor Brown in October 2015. Kansas and Hawaii’s LEAD-K bills were signed into law during Spring 2016. During September 2016, Deaf representatives from 23 states are flew to Sacramento to receive LEAD-K legislative training, led by the LEAD-K campaign director.

“All three legislative achievements were accomplished by the Deaf people in the driver’s seat; this is a Deaf-led movement, which is very empowering for the families and their Deaf children to witness and model after,” says Rems Smario. “The LEAD-K is the answer to ending over 130 years of language deprivation and dismal educational status endured by our Deaf children because it gives the families the knowledge, the tools and the power to enforce language acquisition accountability for their children to be Kindergarten-ready. It is a very exciting time for the families and their Deaf children. “

Using the fame he gained as winner of both America’s Next Top Model and Dancing With the Stars, Nyle DiMarco has been a highly visible advocate for ASL language rights and an ally to the LEAD-K movement. Coming from a Deaf family, DiMarco understands how crucial it is for deaf young people to have language access and role models in the public eye. He endeavors to give back to the community through his non-profit, the Nyle DiMarco Foundation (NDF). DiMarco has become the LEAD-K celebrity spokesperson, and NDF and offers funding for LEAD-K initiatives. According to the NDF website, “The Nyle DiMarco Foundation’s mission is to empower positive Deaf Identities in all aspect of life, and we wholeheartedly support [LEAD-K] goal for accurate resources to share with families, professionals and communities. With the Nyle DiMarco foundation, we can continue onward to create new generations of Kindergarten-Ready Deaf Kids!”

Using the fame he gained as winner of both America’s Next Top Model and Dancing With the Stars, Nyle DiMarco has been a highly visible advocate for ASL language rights and an ally to the LEAD-K movement. Coming from a Deaf family, DiMarco understands how crucial it is for deaf young people to have language access and role models in the public eye. He endeavors to give back to the community through his non-profit, the Nyle DiMarco Foundation (NDF). DiMarco has become the LEAD-K celebrity spokesperson, and NDF and offers funding for LEAD-K initiatives. According to the NDF website, “The Nyle DiMarco Foundation’s mission is to empower positive Deaf Identities in all aspect of life, and we wholeheartedly support [LEAD-K] goal for accurate resources to share with families, professionals and communities. With the Nyle DiMarco foundation, we can continue onward to create new generations of Kindergarten-Ready Deaf Kids!”

Meeting Diverse Educational Needs

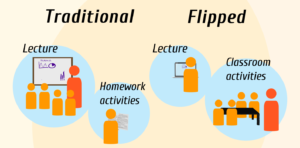

Early intervention creates a strong foundation, but education does not stop in Kindergarten. How do we help the deaf kids already in classrooms throughout the country? The needs of students who are deaf/ HoH can best be met through a variety of different educational strategies, some of which could very easily be implemented to the benefit of all students. Recently Gary Behm, Director at the Center on Access Technology Innovation Laboratory at National Technical Institute for the Deaf (NTID), offered to explain one effective classroom strategy that is utilized for deaf students at NTID.

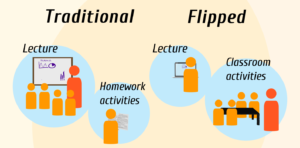

“This program is specifically targeting less lecture in classrooms and more hands-on work and discussion. Teachers will record themselves doing a lecture and students can watch the lecture at home, then they go back to classroom and focus on hands-on aspects. The program is called Flipped Course,” said Behm. “In the DeafTEC program, the Flipped Course lectures themselves are deaf professors from all different fields. Students are using those videos for lectures, and then using classroom for discussion. There are many older deaf teachers that are retired, so we are trying to use their skills.”

By offering students a variety of classroom strategies, educators are able to effectively acknowledge the diversity of their students. Adopting new techniques is possible in any educational program but in mainstream settings, even with an IEP, the resources to create high quality deaf-specific curriculum are generally lacking. Rolling out something like a Flipped Course can be done anywhere, but it is most efficient in a situation where it meets the needs of many students— once again highlighting the true value of schools for the deaf.

Looking to the Future

Gallaudet University estimates that “anywhere from 9 to 22 out of every 1,000 people have a severe hearing impairment or are deaf.” These numbers reflect a small but still significant segment of the population. And, like most marginalized groups, people who are deaf often find themselves struggling for upward mobility within a system that was not designed for their success. As individuals we can only do so much to remedy the injustices of society, but together we can create real and lasting change.

Gallaudet University estimates that “anywhere from 9 to 22 out of every 1,000 people have a severe hearing impairment or are deaf.” These numbers reflect a small but still significant segment of the population. And, like most marginalized groups, people who are deaf often find themselves struggling for upward mobility within a system that was not designed for their success. As individuals we can only do so much to remedy the injustices of society, but together we can create real and lasting change.

Through raising awareness, educating, and offering valid platforms to deaf individuals to share their experiences, hopefully we can soon see a shift in the educational landscape that offers more fruitful opportunities to those who are deaf. After more than 130 years of oppression, deaf advocates are reclaiming the reigns and spearheading much needed educational reform measures. By dispelling stereotypes and falsehoods surrounding ASL and language acquisition, deaf advocates strive to break the cycle of oppression that keeps deaf individuals out of classrooms, boardrooms, and legislative positions.

In the year 2016, one might assume that education for those who are d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing has advanced to the point where deaf young people in America are receiving the same level of education as their hearing peers. One might assume that federal legislation such as the

In the year 2016, one might assume that education for those who are d/Deaf and Hard of Hearing has advanced to the point where deaf young people in America are receiving the same level of education as their hearing peers. One might assume that federal legislation such as the  Access to education is an issue that most people who are deaf/ HoH begin to face long before they set foot in a school. Since 9 out of 10 deaf children are born to hearing families, these kids often begin their journey without acquiring basic communication skills, as their families don’t use sign language. Deaf babies who do not have access to a signed language cannot easily articulate their wants and needs with caregivers, and therefore they can become quickly frustrated. Falling behind their hearing peers in early linguistic comprehension causes many deaf youths to face a disadvantage right from the start. This is where schools for the Deaf can make all the difference by offering young deaf children the support they need to develop their language and literacy skills in a specifically structured setting.

Access to education is an issue that most people who are deaf/ HoH begin to face long before they set foot in a school. Since 9 out of 10 deaf children are born to hearing families, these kids often begin their journey without acquiring basic communication skills, as their families don’t use sign language. Deaf babies who do not have access to a signed language cannot easily articulate their wants and needs with caregivers, and therefore they can become quickly frustrated. Falling behind their hearing peers in early linguistic comprehension causes many deaf youths to face a disadvantage right from the start. This is where schools for the Deaf can make all the difference by offering young deaf children the support they need to develop their language and literacy skills in a specifically structured setting. Both

Both  “Placing every deaf child in their respective neighborhood school is not practical, economical, or educationally beneficial,” asserts the NAD position statement. It continues to explain that mainstream schools with few deaf students tend to lack the appropriate resources. “In many states, there are large geographical areas with a small deaf student population, making schools for the deaf a cost-effective means to optimal educational services.”

“Placing every deaf child in their respective neighborhood school is not practical, economical, or educationally beneficial,” asserts the NAD position statement. It continues to explain that mainstream schools with few deaf students tend to lack the appropriate resources. “In many states, there are large geographical areas with a small deaf student population, making schools for the deaf a cost-effective means to optimal educational services.”

Deaf individuals continue to face exponentially higher unemployment rates

Deaf individuals continue to face exponentially higher unemployment rates hearing individuals decided the unfortunate course of deaf education for the next 100+ years. In this modern era, however, deaf people have the technology to connect and organize like never before. We are currently witnessing a major push-back against hearing parties making decisions for the deaf community, with assertive advocates utilizing new communication tools to rally support for proactive deaf-led reform. They are sharing their own experiences with the families of deaf children, alongside supporting research, to help secure better opportunities for generations to come.

hearing individuals decided the unfortunate course of deaf education for the next 100+ years. In this modern era, however, deaf people have the technology to connect and organize like never before. We are currently witnessing a major push-back against hearing parties making decisions for the deaf community, with assertive advocates utilizing new communication tools to rally support for proactive deaf-led reform. They are sharing their own experiences with the families of deaf children, alongside supporting research, to help secure better opportunities for generations to come. Using the fame he gained as winner of both America’s Next Top Model and Dancing With the Stars, Nyle DiMarco has been a highly visible advocate for ASL language rights and an ally to the LEAD-K movement. Coming from a Deaf family, DiMarco understands how crucial it is for deaf young people to have language access and role models in the public eye. He endeavors to give back to the community through his non-profit, the Nyle DiMarco Foundation (NDF). DiMarco has become the LEAD-K celebrity spokesperson, and NDF and offers funding for LEAD-K initiatives. According to the NDF website, “The Nyle DiMarco Foundation’s mission is to empower positive Deaf Identities in all aspect of life, and we wholeheartedly support [LEAD-K] goal for accurate resources to share with families, professionals and communities. With the Nyle DiMarco foundation, we can continue onward to create new generations of Kindergarten-Ready Deaf Kids!”

Using the fame he gained as winner of both America’s Next Top Model and Dancing With the Stars, Nyle DiMarco has been a highly visible advocate for ASL language rights and an ally to the LEAD-K movement. Coming from a Deaf family, DiMarco understands how crucial it is for deaf young people to have language access and role models in the public eye. He endeavors to give back to the community through his non-profit, the Nyle DiMarco Foundation (NDF). DiMarco has become the LEAD-K celebrity spokesperson, and NDF and offers funding for LEAD-K initiatives. According to the NDF website, “The Nyle DiMarco Foundation’s mission is to empower positive Deaf Identities in all aspect of life, and we wholeheartedly support [LEAD-K] goal for accurate resources to share with families, professionals and communities. With the Nyle DiMarco foundation, we can continue onward to create new generations of Kindergarten-Ready Deaf Kids!”