When hearing people think about exciting new technologies for those who are deaf, their minds most likely jump to the latest developments in cochlear implants or hearing aids. Or perhaps they may vaguely recall reading about any number of devices being developed to translate sign language into speech (or speech into ASL, or ASL into text). When hearing people think about deafness in general, they tend to think only in terms of “problems” and “solutions.” Luxury technology now forms a cornerstone of our sleek American culture, yet very few innovations seek to enhance — or even consider — the real diversity of the modern user base.

When hearing people think about exciting new technologies for those who are deaf, their minds most likely jump to the latest developments in cochlear implants or hearing aids. Or perhaps they may vaguely recall reading about any number of devices being developed to translate sign language into speech (or speech into ASL, or ASL into text). When hearing people think about deafness in general, they tend to think only in terms of “problems” and “solutions.” Luxury technology now forms a cornerstone of our sleek American culture, yet very few innovations seek to enhance — or even consider — the real diversity of the modern user base.

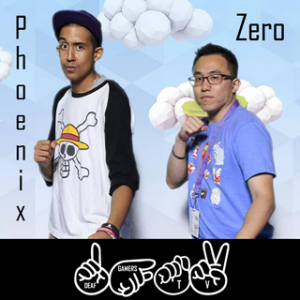

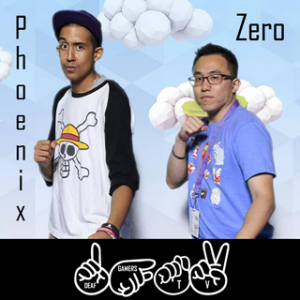

Chris (“Phoenix”) Robinson, who has severe hearing loss in his right ear and is completely deaf in his left, and Brandon (“Zero”) Chan, who is deaf, began their Twitch.tv channel DeafGamersTV with a seemingly simple goal: break down the barrier between deaf and hearing people in the gaming world. Where most gamers take for granted the ability to just log on and join in, Chris and Brandon found themselves kicked off teams and cyber bullied on some platforms simply because they don’t use microphones to communicate. They began the DeafGamersTV channel to educate and raise awareness about deafness in gaming, and to create a community of people who are interested in connecting across languages to have fun!

Chris (“Phoenix”) Robinson, who has severe hearing loss in his right ear and is completely deaf in his left, and Brandon (“Zero”) Chan, who is deaf, began their Twitch.tv channel DeafGamersTV with a seemingly simple goal: break down the barrier between deaf and hearing people in the gaming world. Where most gamers take for granted the ability to just log on and join in, Chris and Brandon found themselves kicked off teams and cyber bullied on some platforms simply because they don’t use microphones to communicate. They began the DeafGamersTV channel to educate and raise awareness about deafness in gaming, and to create a community of people who are interested in connecting across languages to have fun!

Underlying the efforts of the DeafGamers is the audist assumption that people who are deaf do not play video games, and therefore do not need an equal opportunity to participate in the online gaming community. When we look even deeper, we see that assumption across the board when it comes to emerging technologies. It has been assumed that people who are deaf don’t want to watch streamed content, use shortcut features on their devices, or engage in online spaces dominated by hearing individuals. If one barrier to access is the ability to speak and/or hear, then casual socializing, convenience, and luxury are thereby commodities of the hearing majority: even in the “wild west” world of new tech.

Underlying the efforts of the DeafGamers is the audist assumption that people who are deaf do not play video games, and therefore do not need an equal opportunity to participate in the online gaming community. When we look even deeper, we see that assumption across the board when it comes to emerging technologies. It has been assumed that people who are deaf don’t want to watch streamed content, use shortcut features on their devices, or engage in online spaces dominated by hearing individuals. If one barrier to access is the ability to speak and/or hear, then casual socializing, convenience, and luxury are thereby commodities of the hearing majority: even in the “wild west” world of new tech.

Innovators and entrepreneurs have only recently begun to recognize a major void in the market for accessible technologies. The DeafGamers were recently contacted by SubPac, a Los Angeles based company specializing in tactile audio technology that transfers low frequencies (bass) directly to a user’s body. “They provided us with a SubPac vest and SubPac chair strap so we can show how it actually helps us feel the game,” explained Robinson.

Innovators and entrepreneurs have only recently begun to recognize a major void in the market for accessible technologies. The DeafGamers were recently contacted by SubPac, a Los Angeles based company specializing in tactile audio technology that transfers low frequencies (bass) directly to a user’s body. “They provided us with a SubPac vest and SubPac chair strap so we can show how it actually helps us feel the game,” explained Robinson.

The SubPac vests have been used and endorsed by artists, from Deaf dancer Saheem Sanchez to Timbaland. During the Dancing With the Stars season 22 finale, Nyle DiMarco’s friends and family section was equipped with SubPacs so this deaf guests could actually enjoy the sensations of the songs while they watched him perform.

Overseas, The Junge Symphoniker, a symphony orchestra in Hamburg, is utilizing “The Sound Shirt” in their concerts. This wearable device uses strategically placed microphones on the stage to convert the nuanced vibrations of a live symphony orchestra performance into a fully body experience for the person wearing the shirt. Industrial designer Liron Gino recently demoed her prototype for Vibeat, a set of vibrating Bluetooth devices designed to “provide a parallel sensory experience to that which a hearing person might have when using a portable music player with headphones.”

Overseas, The Junge Symphoniker, a symphony orchestra in Hamburg, is utilizing “The Sound Shirt” in their concerts. This wearable device uses strategically placed microphones on the stage to convert the nuanced vibrations of a live symphony orchestra performance into a fully body experience for the person wearing the shirt. Industrial designer Liron Gino recently demoed her prototype for Vibeat, a set of vibrating Bluetooth devices designed to “provide a parallel sensory experience to that which a hearing person might have when using a portable music player with headphones.”

These new devices are part of a growing set of consumer technologies that consider accessibility an asset, instead an inconvenience. This trend demonstrates a shift, however slight, in the way our culture views people who are deaf. No longer perceived as perpetual victims of circumstance whose only desire is communicating with the hearing world; deaf individuals are now being seen as average Americans seeking ways to make life more simple, pleasurable, and fun.

People who are deaf are actively dismantling stereotypes, and technology plays a large role in this movement. DJ Robbie Wilde, who is deaf, utilizes a software program called Serrato that allows him to see the different waveforms when he is mixing and performing. Artist and Senior TED Fellow Christine Sun Kim uses a variety of speakers, paints, projections, lights, balloons and more, to translate sound into electricity and vibrations, and then into visual art. The Signly Keyboard App, backed by non-profit ASLized, brought ASL emojis to a very eager community of deaf texters, offering a more enjoyable and precise way to communicate in their own language.

People who are deaf are actively dismantling stereotypes, and technology plays a large role in this movement. DJ Robbie Wilde, who is deaf, utilizes a software program called Serrato that allows him to see the different waveforms when he is mixing and performing. Artist and Senior TED Fellow Christine Sun Kim uses a variety of speakers, paints, projections, lights, balloons and more, to translate sound into electricity and vibrations, and then into visual art. The Signly Keyboard App, backed by non-profit ASLized, brought ASL emojis to a very eager community of deaf texters, offering a more enjoyable and precise way to communicate in their own language.

Designing technology specifically for use by the deaf community is all well and good in theory, but unfortunately, there is a financial reality to face. The cost of production for new devices can be high, therefore companies like SubPac must find ways to appeal to a wider market.

“I love music and I want deaf people to have the opportunity to experience music,” explains Gary Behm, Director of the RIT/ NTID Center on Access Technology. “But for this type of equipment to be cost-effective, it must also benefit the hearing community. Businesses need to make a profit.”

“I love music and I want deaf people to have the opportunity to experience music,” explains Gary Behm, Director of the RIT/ NTID Center on Access Technology. “But for this type of equipment to be cost-effective, it must also benefit the hearing community. Businesses need to make a profit.”

Behm works with deaf students at NTID to create technologies that help deaf and hard of hearing individuals gain better access to a world designed by, and for, the hearing majority. These students are improving access in homes, businesses, and especially classrooms— opening up an increasing number of opportunities for future generations! Behm says NTID has been very involved in making the STEM field more accessible through educational outreach programs like the Master of Science program in Secondary Education (MSSE), and DeafTEC.

According to the DeafTEC website: “The goal of DeafTEC is to successfully integrate more deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals into the workplace in highly-skilled technician jobs in which these individuals are currently under-represented and underutilized.” Behm emphasizes the importance of laying a strong educational foundation at a young age, and encouraging middle and high school age children who are deaf to explore their interest in technology-related fields. By fostering curiosity and innovation from childhood all the way through higher education, we see the effects ripple out to impact society at large. “Anything that we invent as the deaf will benefit the hearing community as well,’ says Behm.

“The principle of universal design ensures people with disabilities can access your website while improving the experience for people without disabilities,” explains David Peter, a software developer who is deaf, in his article for Model View Culture. “Universal design has its roots in architecture; wheelchair users cannot climb sidewalks, so sidewalks dropped their curbs — this also benefitted, among others, skateboarders and parents pushing strollers….If we want the best product experience, accessibility must always be considered a line-item, just like you would consider security, performance, and internationalization.”

“The principle of universal design ensures people with disabilities can access your website while improving the experience for people without disabilities,” explains David Peter, a software developer who is deaf, in his article for Model View Culture. “Universal design has its roots in architecture; wheelchair users cannot climb sidewalks, so sidewalks dropped their curbs — this also benefitted, among others, skateboarders and parents pushing strollers….If we want the best product experience, accessibility must always be considered a line-item, just like you would consider security, performance, and internationalization.”

With more community members using mainstream platforms to advocate for access, and an increasing number of d/Deaf individuals choosing STEM careers, the technological landscape is adjusting to the reality that people who are deaf use technology just as much, if not more, than everyone else. From smartphone apps to fancy new devices, companies that demonstrate an appreciation for diversity by building accessibility right into their products are sure to gain larger numbers of loyal users. After being disenfranchised and overlooked for too long, people who are deaf are using technology to build a future that actually includes them.

When hearing people think about exciting new technologies for those who are deaf, their minds most likely jump to the latest developments in cochlear implants or hearing aids. Or perhaps they may vaguely recall reading about any number of devices being developed to translate sign language into speech (or speech into ASL, or ASL into text). When hearing people think about deafness in general, they tend to think only in terms of “problems” and “solutions.” Luxury technology now forms a cornerstone of our sleek American culture, yet very few innovations seek to enhance — or even consider — the real diversity of the modern user base.

When hearing people think about exciting new technologies for those who are deaf, their minds most likely jump to the latest developments in cochlear implants or hearing aids. Or perhaps they may vaguely recall reading about any number of devices being developed to translate sign language into speech (or speech into ASL, or ASL into text). When hearing people think about deafness in general, they tend to think only in terms of “problems” and “solutions.” Luxury technology now forms a cornerstone of our sleek American culture, yet very few innovations seek to enhance — or even consider — the real diversity of the modern user base. Chris (“Phoenix”) Robinson, who has severe hearing loss in his right ear and is completely deaf in his left, and Brandon (“Zero”) Chan, who is deaf, began their Twitch.tv channel

Chris (“Phoenix”) Robinson, who has severe hearing loss in his right ear and is completely deaf in his left, and Brandon (“Zero”) Chan, who is deaf, began their Twitch.tv channel

Innovators and entrepreneurs have only recently begun to recognize a major void in the market for accessible technologies. The DeafGamers were recently contacted by SubPac, a Los Angeles based company specializing in tactile audio technology that transfers low frequencies (bass) directly to a user’s body. “They provided us with a SubPac vest and SubPac chair strap so we can show how it actually helps us feel the game,” explained Robinson.

Innovators and entrepreneurs have only recently begun to recognize a major void in the market for accessible technologies. The DeafGamers were recently contacted by SubPac, a Los Angeles based company specializing in tactile audio technology that transfers low frequencies (bass) directly to a user’s body. “They provided us with a SubPac vest and SubPac chair strap so we can show how it actually helps us feel the game,” explained Robinson. Overseas, The Junge Symphoniker, a symphony orchestra in Hamburg, is utilizing “

Overseas, The Junge Symphoniker, a symphony orchestra in Hamburg, is utilizing “ People who are deaf are actively dismantling stereotypes, and technology plays a large role in this movement. DJ Robbie Wilde, who is deaf, utilizes a software program called Serrato that allows him to see the different waveforms when he is mixing and performing. Artist and Senior TED Fellow Christine Sun Kim uses a variety of speakers, paints, projections, lights, balloons and more, to translate sound into electricity and vibrations, and then into visual art. The Signly Keyboard App, backed by non-profit ASLized, brought ASL emojis to a very eager community of deaf texters, offering a more enjoyable and precise way to communicate in their own language.

People who are deaf are actively dismantling stereotypes, and technology plays a large role in this movement. DJ Robbie Wilde, who is deaf, utilizes a software program called Serrato that allows him to see the different waveforms when he is mixing and performing. Artist and Senior TED Fellow Christine Sun Kim uses a variety of speakers, paints, projections, lights, balloons and more, to translate sound into electricity and vibrations, and then into visual art. The Signly Keyboard App, backed by non-profit ASLized, brought ASL emojis to a very eager community of deaf texters, offering a more enjoyable and precise way to communicate in their own language. “I love music and I want deaf people to have the opportunity to experience music,” explains Gary Behm, Director of the RIT/ NTID Center on Access Technology. “But for this type of equipment to be cost-effective, it must also benefit the hearing community. Businesses need to make a profit.”

“I love music and I want deaf people to have the opportunity to experience music,” explains Gary Behm, Director of the RIT/ NTID Center on Access Technology. “But for this type of equipment to be cost-effective, it must also benefit the hearing community. Businesses need to make a profit.” “The principle of universal design ensures people with disabilities can access your website while improving the experience for people without disabilities,” explains David Peter, a software developer who is deaf, in his article for

“The principle of universal design ensures people with disabilities can access your website while improving the experience for people without disabilities,” explains David Peter, a software developer who is deaf, in his article for